What is alchemy? Alchemy is most well-known for its attempts to change common metals into silver and gold. Yet is an ancient discipline originally studied in Egypt and the Greek Hellenistic empire, China and India.

The origins of alchemy

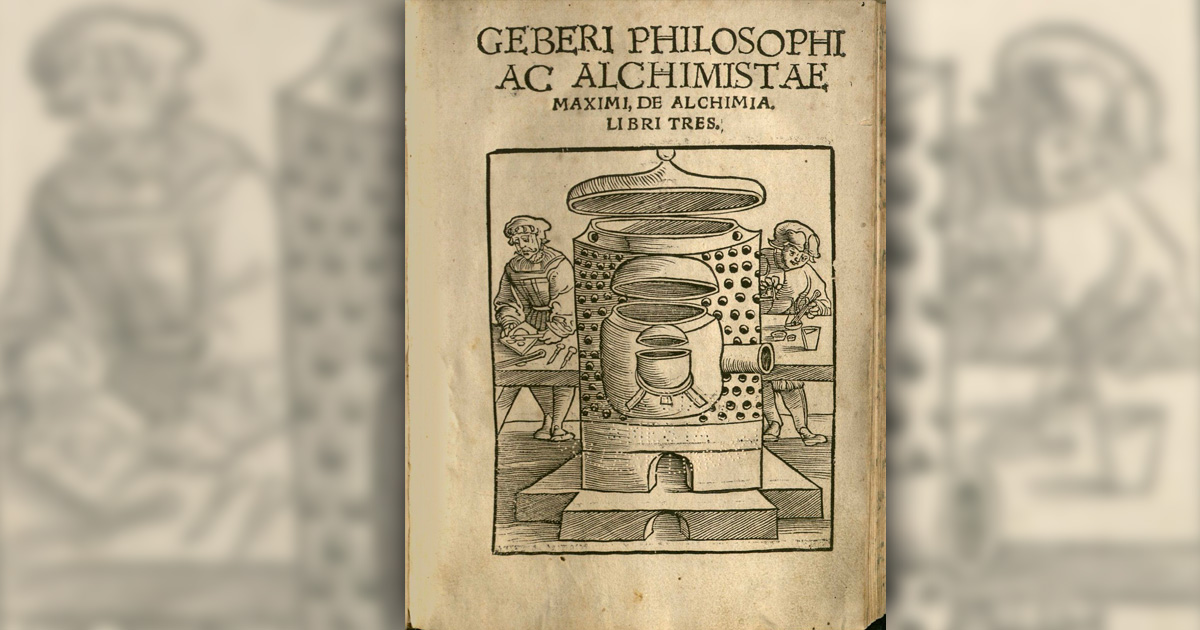

Alchemy came to Western Europe from the Islamic kingdoms in the twelfth century. Arabic alchemical books were initially translated by the Christian church. Its ideas of transmutation became increasingly popular. Interest in alchemical gold peaked between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries at a time of numerous famines and wars and a great need for money to fund them. Yet alchemy was more than just a fantastical get-rich-quick scheme. It combined ideas from early science and medicine with religious and metaphysical beliefs.

Alchemists wanted to change one thing into another. In order to do this, practitioners first had to think about what their substances were made up of and how they could alter them. In the days before modern science, alchemy was one way to think about the world and try to understand how it worked. By the late sixteenth century alchemy was regarded as a serious scientific and philosophical pursuit, despite its controversial nature. Leading scientific thinkers of the day such as Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton studied alchemy. Newton wrote more than a million words about it.

Theories of alchemy

There was no schools or guilds of alchemists with authorised teachings. This meant that there were many different theories and ideas about how alchemy worked.

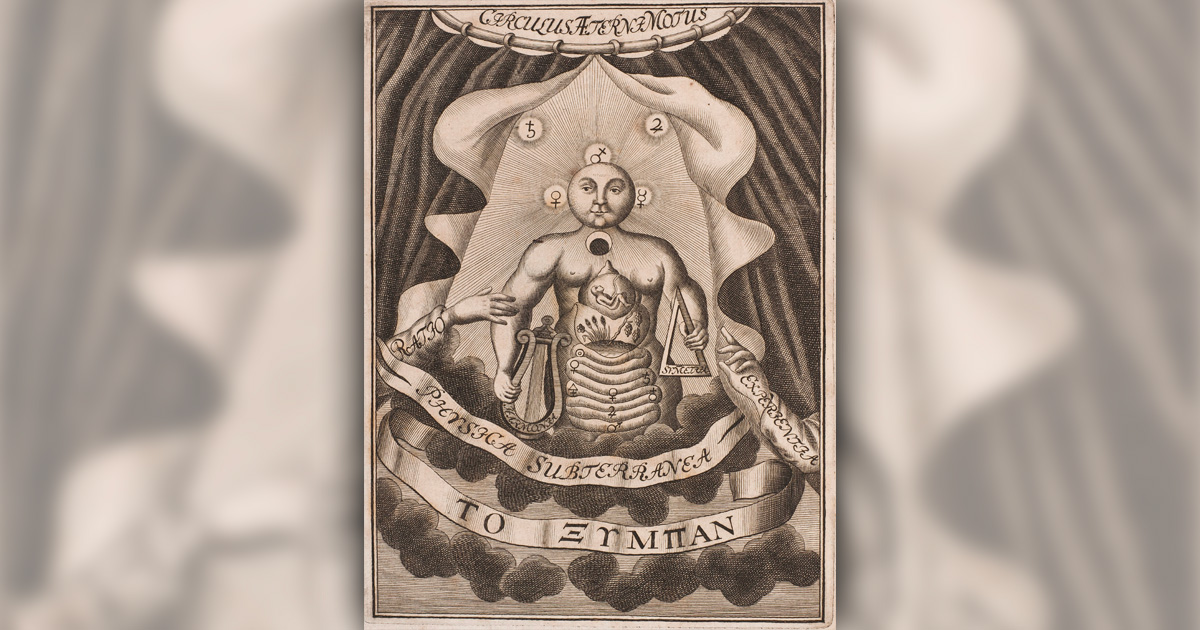

Alchemists believed that everything was made up of the four elements of earth, air, fire and water. This was originally a Greek idea, from the philosopher Aristotle, who also believed that the universe was divided into two parts – heaven and earth. What happened in heaven was reflected on the earth below. Alchemists thought the planets were connected to different metals on earth, for example gold was with linked with the sun and its associated properties.

Most people believed that metals were seeded deep into the earth by God when he created the world. Miners noticed that metal ores ran through rocks in veins that looked like plant roots, growing and spreading. Alchemists took this idea a step further. They believed that common metals like iron and lead could develop and mature into silver and then gold as the most perfect of all metals. Alchemists thought they could recreate this process of growth using the Philosopher’s Stone to turn common metals into gold.

The Philosopher’s Stone

Alchemists believed the Philosopher’s Stone had the power of transmutation and could be used to change metal into gold. They called this the ‘Great Work’ or ‘Magnum Opus’. Some alchemists thought the Philosopher’s Stone could also be an elixir or medicine that could extend their life and heal all diseases. They called this ‘potable’ or drinkable gold. Others saw the Philosopher’s Stone as a way to seek enlightenment and a higher spirituality. All they needed to do was find the right alchemical recipe to create it.

Alchemical ingredients

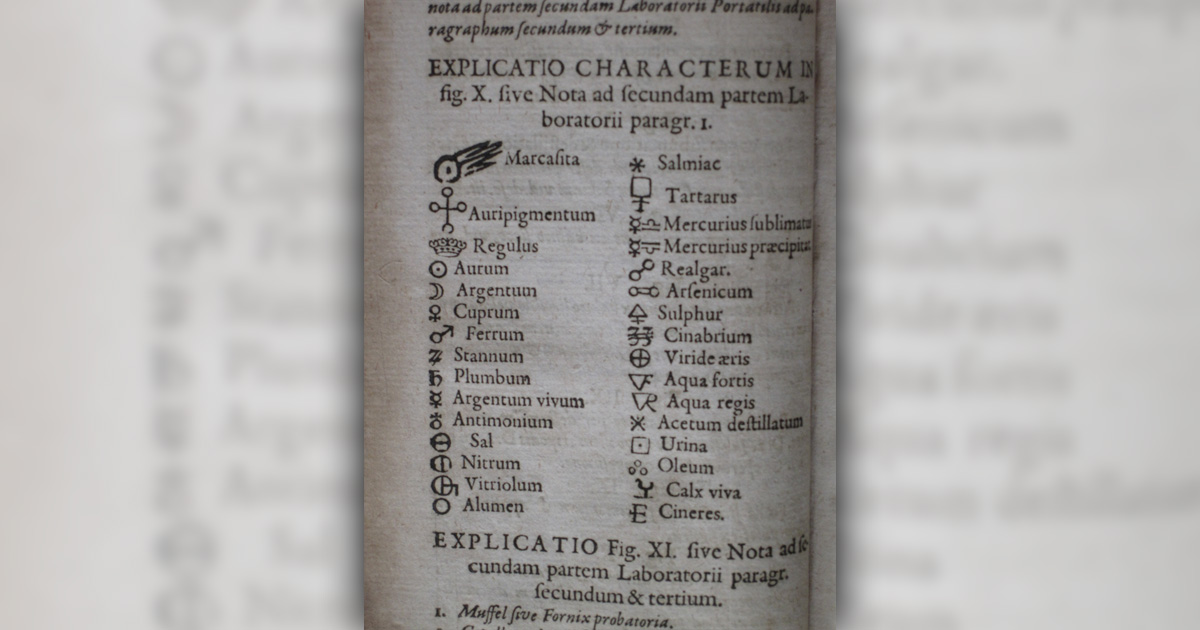

Alchemists used a wide range of materials in their quest for alchemical gold. Books and manuscripts list common ingredients such as metals, minerals like saltpetre and strong acids to dissolve substances so they could be added to the mix. Organic matter might include blood, hair and urine.

Other ingredients are more puzzling. Alchemical recipes often list ‘philosophical’ sulphur and mercury. These were not simply chemicals but somehow embodied certain properties that also needed to be combined to create the Philosopher’s Stone. For example, philosophical mercury was considered to contain female, silver and lunar principles. Alchemists sought to combine both the physical and metaphysical properties in their ingredients.

Alchemical processes

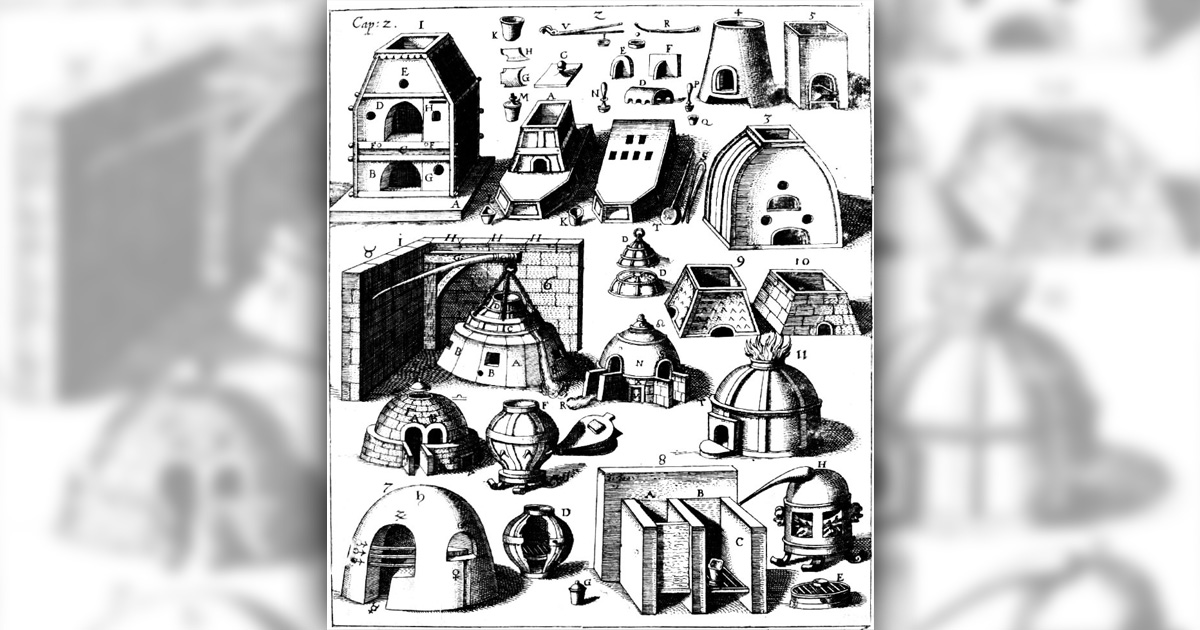

Once the alchemist had the right ingredients, the next step was to mix them up in the correct combination and then apply several different types of alchemical processes to them. These processes combined alchemical ideas with chemical operations. For example, the first process often involved calcination, which is when material is heated until it’s reduced to ashes. This also reflected the alchemical idea that matter had to be broken down into a basic, primal mass before reforming it into a higher state.

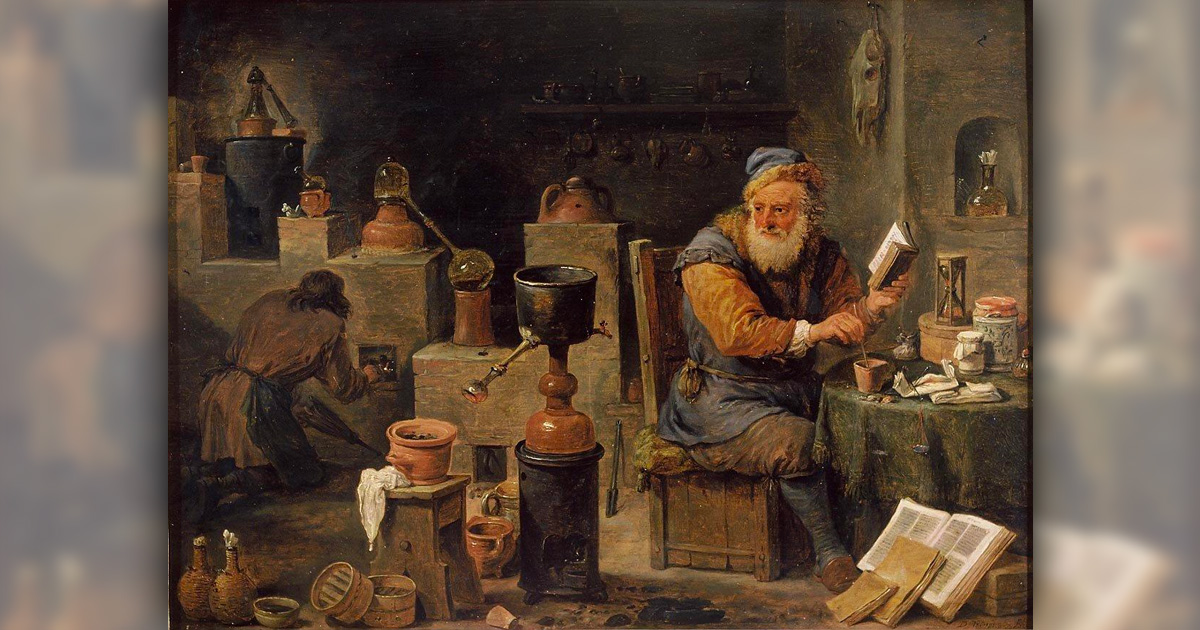

Alchemists used furnaces to control the amount of heat applied to their mixtures and carefully designed vessels and flasks to distil their ingredients by repeatedly boiling and condensing them.

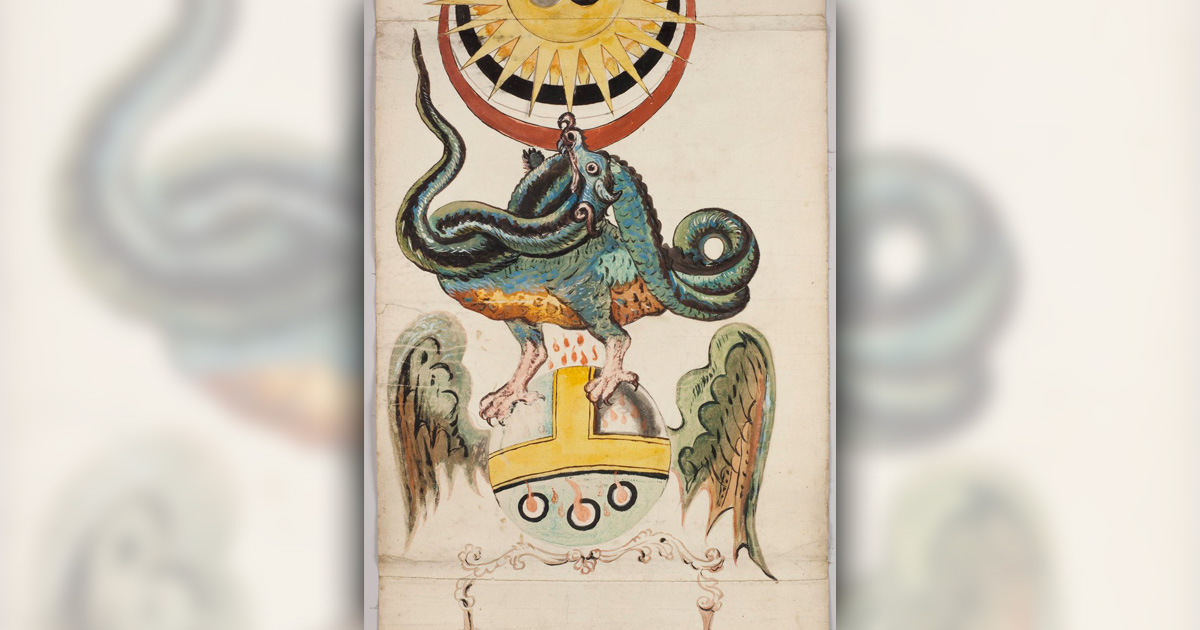

Whilst alchemists couldn’t agree on exactly what processes were involved, most thought that their mixture had to go through several different colour changes as part of the recipe. The first stage produced black matter which then became white as the ingredients were purified. The heat of furnace was increased to turn the substance red, showing that the alchemist had successfully created the Philosopher’s Stone.

Who practiced alchemy?

In popular culture, alchemists are often shown as wise old men with long beards, labouring away in a dark and smoky laboratory. In reality alchemy was practised by a wide range of people. Some devoted their lives to alchemy and sought rich patrons to fund them. Those who were successful might be rewarded with supplies and equipment. However, if they failed, alchemists could be taken to court or worse. Duke Friedrick of Württemburg (1557–1608) in Germany found it particularly amusing to hang alchemical fraudsters on a gold plated gallows.

Many alchemists were priests and monks. They believed their alchemical work was done with the permission of God and their research revealed the truth of God’s creation. Some alchemists sought the Philosopher’s Stone in order to receive religious enlightenment.

Kings and rulers could see the economic advantage of creating alchemical gold. Some monarchs tried to control alchemy by making it illegal without a special license – granted by them. Others encouraged alchemists to come to their court where they could keep an eye on them, sometimes with unpredictable results. The alchemist Sendivogius’ experiments at the court of Rudolf II in Krakow allegedly set the place on fire causing the King to move to Warsaw, where it became the capitol of Poland.

Alchemists might also be merchants, aristocrats, scholars, doctors, craft-workers, soldiers and cooks. Female authors wrote a number of alchemical books and manuscripts. Noblewomen were patrons and employers of alchemists. Some women used alchemical practices as part of their housekeeping duties.

Knowledge of alchemy was not just limited to its practitioners. Alchemical books and texts became increasingly popular in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and so its ideas came to spread throughout literature, theatre and the arts. You can find alchemical themes and ideas in Shakespeare, Chaucer and Milton’s works as well as alchemical images in paintings and architecture.

Symbolism and secrecy

Alchemy was a secret art right from its ancient origins. Texts warned their readers not to share their knowledge because it was too dangerous for the ignorant. So when alchemy arrived in Western Europe, authors continued to write down their recipes using codes and complicated metaphors to disguise their ingredients and practices. This protected their secrets as only another alchemist would be able to understand their words.

As the technology to print text and illustrations improved, alchemical books began to include drawings to accompany their recipes. Alchemists used symbolic images to represent and conceal their ingredients and instructions. These pictures were often a strange mix of emblems from the natural world, mythology and Christianity. They sometimes used startling combinations of sex, death and violence to symbolise chemical processes such as joining ingredients together or the symbolic death of substances into a blackened mass. The final red stage of the Philosopher’s Stone was often shown as a fiery phoenix, resurrected from the dead and able to transform metals into gold.

The legacy of alchemy

Alchemists continually tried different ingredients, combinations and chemical processes in their quest for alchemical gold. As a result they discovered considerable information about chemicals and other substances. An alchemist named Hennig Brand discovered a new element in his search for the Philosopher’s Stone in 1669. After experiments with the residues from boiled-down urine, Brand found a white substance that glowed in the dark and burnt brilliantly. He named it phosphorus mirabilis meaning miraculous bearer of light. It was the first element discovered since antiquity.

Alchemical knowledge was used in medicine – informing the first uses of chemotherapy – and many other trades such as glass-working, mining and metal-working. However as alchemical beliefs about the structure of matter were disapproved by the first modern chemists, alchemy ceased to be a serious scientific pursuit. However, it has continued to influence our culture in psychology, art, literature and cinema – most notably the Harry Potter films. Alchemy, it seems, continues to transmute and change to remain a part of our society.

References

- Battistini, Matilde; translated by Rosanna M. Giammanco Frongia. 2007. Astrology, magic, and alchemy in art. J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles.

- Edson, Gary. 2012. Mysticism and alchemy through the ages : the quest for transformation. McFarland & Company. London.

- Greenberg, Arthur. 2007. From alchemy to chemistry in picture and story. Wiley. New Jersey.

- Linden, Stanton J. 2007. Mystical metal of gold : essays on alchemy and Renaissance culture. AMS Press. New York.

- Newman, William Royall. 2006. Atoms and alchemy : chymistry and the experimental origins of the scientific revolution. University of Chicago Press. London.

- Principe, Lawrence. 2013. The secrets of alchemy. University of Chicago Press. London.

Relevant links

Other articles you may be interested in